ORKNEY - LAND OF THE VIKINGS

The Orkney Islands county flag - strongly influenced by ancient links with Norway. It was finally recognised by the Lord Lyon of Scotland and registered on 10 April 2007.

![Vikings [2]](https://www.menwithcuster.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Vikings-2.jpg)

The Orkney Islands were part of the kingdom of Denmark (which included Norway) until as late as 1472 when by act of parliament they were annexed to the Scottish crown.

- Although Orkney’s long held claim that George Armstrong Custer was one of its most famous descendants has proved to be unfounded, circumstantial evidence suggests the legendary General may well have ridden to his death on the bluffs above the Little Big Horn River, Montana Territory, firm in the belief that his ancestors came not from Germany’s Rhineland but were members of an ancient family which had flourished for countless generations in these windswept Nordic isles lying off the north-eastern tip of mainland Scotland – we shall never know.

- Over time this page will be expanded to include a selection of articles relating to Orkney which contain either an international or a military topic and have been previously featured in one or more of the following publications: The Scots Magazine, The Orkney View, The Orcadian newspaper, Sib Folk News, the quarterly newsletter of the Orkney Family History Society, national newspapers and regional journals. Peter Groundwater Russell – 13 November 2016.

- ______________________

- 1. WILLIAM SHEARER – Twice “blown up at sea” and survived to tell the tale!

- 2. IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF WASHINGTON IRVING – retracing his search for the Boar’s Head Tavern, Eastcheap, London.

- 3. A SYMBOL OF HOME AND FRIENDSHIP – reminiscences of Toc H in wartime Orkney.

- 4. A CLASH OF CULTURES AT RED RIVER – The Foss-Pelly Affair.

- 5. CANADA BECKONED – AT £17 A YEAR – The Life of Andrew Groundwater.

Number One - WILLIAM SHEARER - Twice "blown up at sea" and survived to tell the tale!

Royal Navy White Ensign.

Lancashire County Flag.

- I suspect that relatively few mariners survived the traumatic experience of being twice “blown up at sea” during wartime, and yet this is precisely what happened to my Great-uncle William “Billy” Shearer from the parish of Orphir, in the west Mainland of Orkney, a group of islands lying off the north-east tip of Scotland.

- He was born on 18 March 1879 at the Cot of Roadside, a seven-acre holding in the district of Smoogro, which his grandfather, Andrew Groundwater, leased from Dr Charles Still of Burgar, a retired army surgeon. Later the same year the family moved to a small croft called Aikislay in the same parish, near the Loch of Kirbister (formerly Loch of Groundwater), where William’s parents, William Muir Shearer, a ploughman, and Mary Groundwater, were to have eleven more children, the second of which was Margaret, my paternal grandmother.

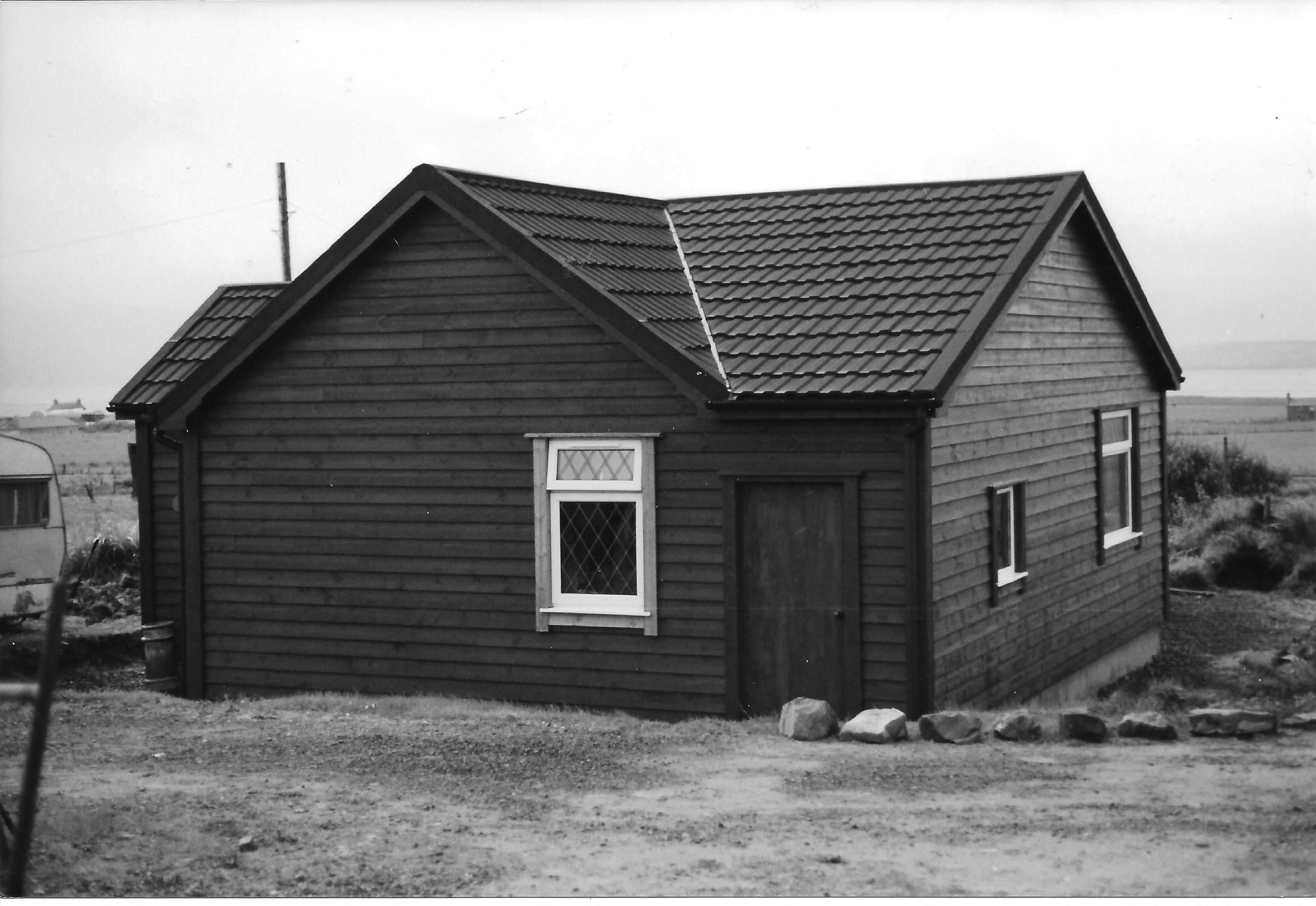

Cot of Roadside, Smoogro, Orphir, Orkney, birthplace of William Shearer.

- While still only 15 years of age an adventurous young William enlisted in the Royal Navy and joined HMS Caledonia (originally HMS Impregnable, built 1810), the boy cadet training ship, that was anchored off Queensferry in the Firth of Forth, near Edinburgh. He served 11 years with the Fleet, three of these being spent patrolling the temperate waters of the Mediterranean. In 1901 he was stationed at HMS Wildfire, the RN Gunnery School at Sheerness, on the Isle of Sheppey, in Kent.

- The final period of his service in the Navy was spent in Chatham, Kent and, it was around the time of his honourable discharge that he wed 24 year-old Winifred ‘Winnie’ Ann Brooks, a cotton spinner, daughter of John Brooks, a blacksmith’s striker, and Margaret Holden, from Preston. They were married in Bromley, also in Kent, in 1905 and moved to Leith, a suburb of Edinburgh. Initially William worked in the docks but when their first child, Winifred Ann (b. 1906), was born he found more secure employment as a postman with the GPO in the Scottish capital. Some twelve months later he was transferred to Blackburn, where Winifred had four more children – William (b. 1907, died in infancy); Victor (b. 1909); Ruby (b. 1913); and Elizabeth (b. 1918). The Census taken on the night of 2 April 1911 found the family living in 49 Scotland Road, Blackburn when William was recorded as a postman and Winifred a cotton weaver in a local mill..

- At the outbreak of the First World War William Shearer was called up along with thousands of other reservists, and from the very beginning Fortune smiled on him. He joined the 12,000-ton cruiser HMS Cressy as a leading seaman but was almost immediately recalled to the depot. A few weeks later the Cressy and two other cruisers were sunk off the Belgian coast with heavy loss of life. His next ship was the Duchess of Devonshire, an armed boarding steamer working in the English Channel.

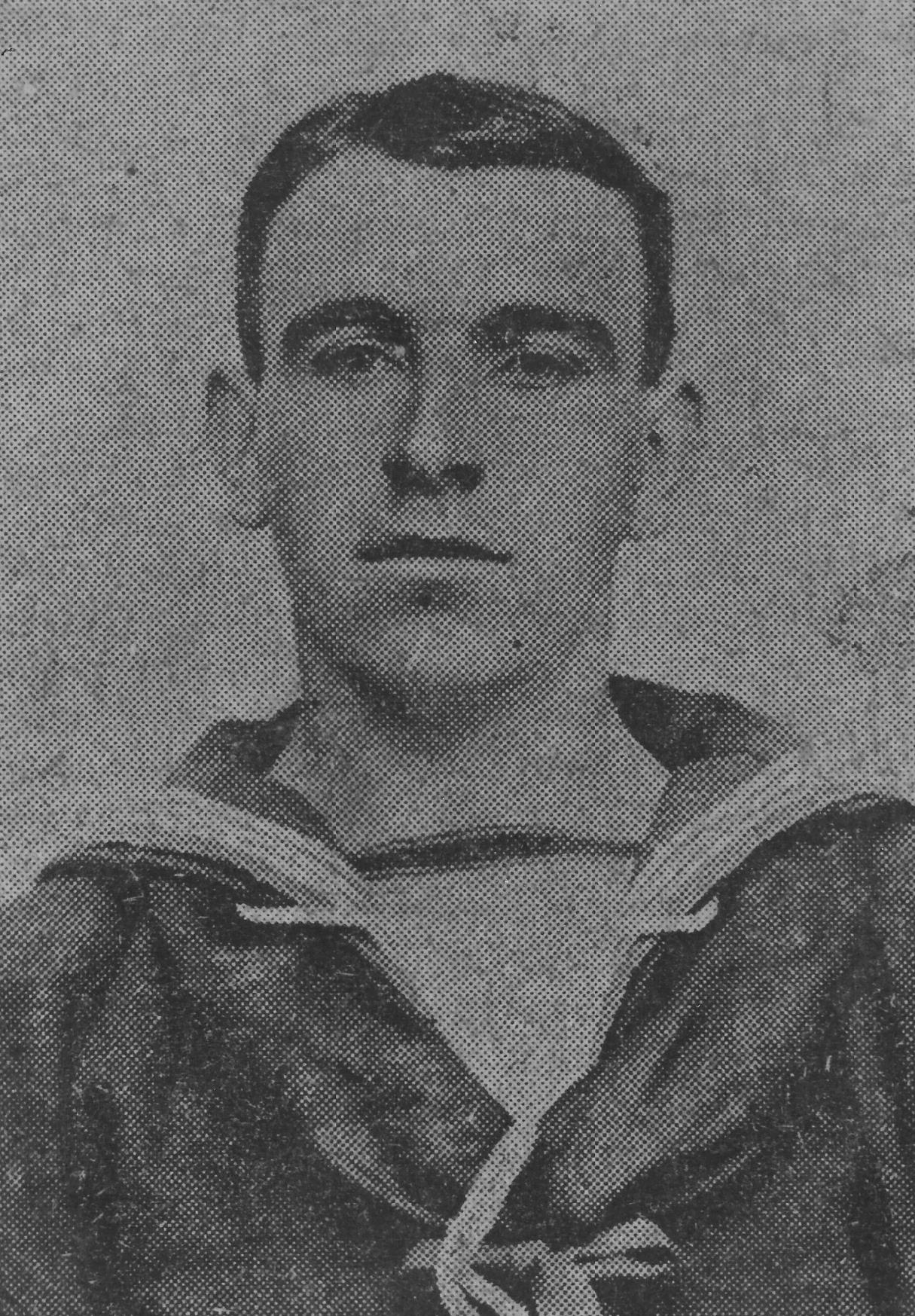

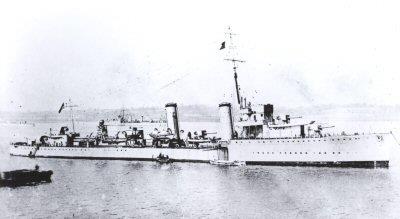

Leading Seaman William Shearer, Royal Navy, photograph taken from 'The Orkney Herald,' 1916 (right). HMS Scott launched 18 October 1917, sunk 15 August 1918 (above)

- Towards the end of 1916 William Shearer was posted to Scapa Flow, Orkney, where he joined HMS Negro, a 1,025-ton ‘M’ class destroyer; the vessel on which he was to have his most nerve-racking experience. In December that year Sir David Beatty, Commander-in-Chief Grand Fleet, decided to take the fleet out into the North Sea and the events that followed are best told in Shearer’s own words as reported in The Orkney Herald, 4 April 1934:

- [On 21 December 1916] “We left the Fleet somewhere north of the Fair Isle to escort another vessel [the Hoste, a 1,666-ton flotilla leader] back to the [Scapa] Flow. It was a dark night, freezing cold and stormy. We were just off Fair Isle when it happened. The fellow we were escorting dropped a depth charge, whether through carelessness or otherwise nobody ever quite found out, but anyway we planted our bow on to it and it blew us up as completely as if we had been torpedoed. In fact we supposed it was a torpedo at the time.

- “An attempt was made to launch the boats, but it was no use. It was evident that the Negro was done for, and we saw that the ship we were escorting had also received the benefit of the explosion and was sinking fast. She had her searchlight on and I saw her going down from the fo’c’sle of the Negro…………Our masts were broken and trailing overboard, and we were settling in the water. It was apparent we might go at any moment. I jumped just a few minutes before the Negro went down, and it looked as if I was out of the frying pan into the fire. The water was icy, and it was all I could do to hang on to the bits of wreckage that was floating about.

- “It was half-an-hour before I was picked up by the Marmion (also an ‘M’ class destroyer), which came to our rescue. She was just in time. Another ten seconds would have finished me. Only thirty-four of us were saved out of a crew of eighty-five. The heart-rending sounds of drowning shipmates crying out for their mothers will haunt me for the rest of my days.” [see note below]

- After this traumatic experience Shearer was given ten days survivor’s leave. His next posting was on the P.20, a 613-ton armed patrol boat, which was engaged on escort duty with the Dover Patrol. Early in 1918 he joined the crew of HMS Scott, a 1,801-ton Scott class flotilla leader, one of the most modern and largest vessels of her class that saw service in the First World War. She was commanded by the Hon. William Spencer Leveson-Gower (pronounce ‘Loosen-Gore’), who curiously enough, had been captain of the Marmion. It was while he was on the Scott, as a gunlayer, that Shearer was ‘blown up’ for the second time.

- On 15 August 1918, while on patrol off the Hook of Holland, the Scott and the Ulleswater (a 921- ton ‘R’ class destroyer) were both torpedoed by a German submarine. The Scott was in the act of rescuing survivors from the Ulleswater when she herself was hit and actually sank before the ship she was attending.

- “This was a picnic compared with the Negro affair,” said Shearer. “Only twenty-nine of the Scott’s 164-strong crew were lost. The rest of us were picked up quite easily, as it was a fine day and the sea was calm. The tragedy of the Scott, as far as I was concerned, was that I lost my bagpipes, but the captain heard of my loss, and presented me with a new set, which I still possess.” Captain Leveson-Gower was married to Lady Rose Bowes-Lyon, daughter of the 14th Earl of Strathmore, which made him an uncle of the Queen! He died in 1953, the year of her coronation.

- Shearer had learned to play the bagpipes during his first spell in the Navy and his skill as a piper was a byword in the Blackburn area, where over a period spanning more than forty years he performed the time-honoured ceremony of “Piping in the Haggis” at Burns Suppers. He always took great pride in his appearance and looked resplendent in the full highland dress of Clan Gunn, whose motto, “Either peace or war,” seemed especially appropriate.

A much-modernised Cornesquoy Cottage, Orphir, Orkney, overlooking Scapa Flow.

- After the cessation of hostilities he returned to work as a postman in Blackburn with the GPO and remained in its employ until reaching the age of fifty-five, when he elected to take early retirement. It had long been his dream to return to live in Orkney.

- “It has always been my intention to permanently reside in my native islands when I retired,” he told a reporter on the Orkney Herald, 31 March 1934. “I am returning to Orkney because I am, and have always been, an Orkney lover. I have frequently visited the county during holidays from my work, and have many friends in my native parish and throughout the isles.”

- William and Winifred rented a four-roomed wooden hut, grandly named ‘Cornesquoy’, that had originally served as officers’ quarters at the nearby Houton army camp during the First World War. Cornesquoy is situated in the remote district of Clestrain in Orphir and lies some six miles from the port of Stromness and twice as far from the county town of Kirkwall. It is not entirely surprising therefore to learn that city-born Winnie was unable to adapt to living in such a ‘godforsaken place’. Apparently she would spend many a lonely hour gazing out of the window, not at the majestic grandeur of the hills of Hoy but in the oft-forlorn hope of seeing the postman making his way up the rough track leading from the distant Stromness-Kirkwall road to deliver a much-awaited letter from her family and friends in faraway Blackburn. Almost inevitably, William Shearer’s lifelong dream of being back in Orkney was soon shattered and in less than eighteen months of their arrival in the islands, the disenchanted couple gathered up their belongings and returned south to Blackburn.

A young William Shearer in full highland dress - date unknown.

William Shearer in later life - date unknown.

- He devoted the rest of his life to his children, grandchildren, the local Presbyterian Church and passing on his piping skills to a younger generation. The old salt finally ‘crossed the bar’ at the age of 77 on 22 April 1956. Although he had spent the greater part of his life in Blackburn, and his mortal remains were laid to rest among ‘the dark, Satanic Mills’ of industrial Lancashire, I believe that Great-uncle Billy’s spirit will dwell forever in his beloved Orkney Isles.

- This paper is an updated and amended version of an article that was first published in The Orkney View magazine and later republished in Sib Folk News, the quarterly newsletter of the Orkney Family History Society. It can also be found on the website of ‘Cotton Town’, local history of Blackburn and Darwen, Lancashire’.

- The sinking of HMS Hoste and HMS Negro

- HMS Hoste joined the Thirteenth Destroyer Flotilla, part of the Grand Fleet, with the pennant number G90. On 19 December 1916, the Grand Fleet left Scapa Flow to carry out exercises between the Shetlands and Norway. On the morning of 20 December, Hoste suffered a failure of her steering gear at high speed, almost colliding with several other ships, and was detached to return to Scapa with the destroyer Negro as escort. At about 01:30 hr on 21 December, in extremely poor weather, with gale-force winds and a heavy sea, Hoste‘s rudder jammed again, forcing the ship into a sudden turn to port. Negro, following about 400 yards behind, collided with Hoste. The collision knocked two depth charges off Hoste‘s stern which exploded, badly damaging the rear end of Hoste and blowing in the bottom of Negro‘s hull, flooding her engine room. Negro sank quickly, and despite the efforts of the destroyer Marmion to rescue survivors, 51 officers and men of Negro‘s crew were killed. Marmion and Marvel attempted to tow the crippled Hoste back to Scapa, but after three hours, Hoste began to founder. Despite the severe conditions, Marvel went alongside Hoste to rescue the crew of the sinking ship, and when repeatedly forced apart by the heavy seas, repeated the manoeuvre another twelve times. While Marvel sustained damage to her forecastle from repeated impacts between the two ships, she managed to rescue all but four of Hoste‘s crew before Hoste finally sank. Eight officers and 126 men were rescued by Marvel. (Source: Wikipedia)

Number Two - IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF WASHINGTON IRVING - retracing his search for the Boar's Head Tavern, Eastcheap, London

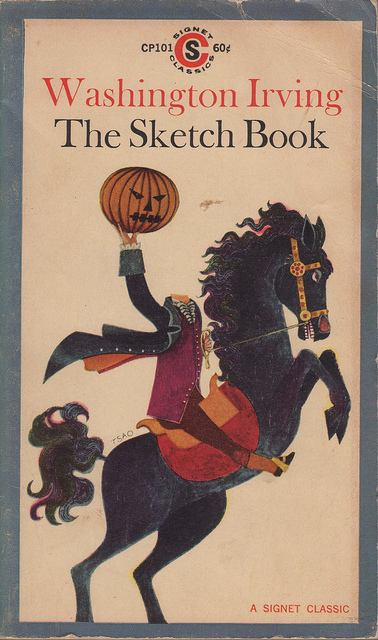

- The exciting prospect of visiting Sleepy Hollow and the enchanting Catskill Mountains while driving from Montreal to New York in the summer of 1994 reminded me that it had been far too long since I had read Washington Irving’s best known work, The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. This is a volume which had first captured my imagination some twenty years before and I was pleased to find that it had lost none of its original appeal. Those immortal characters Ichabod Crane and Rip Van Winkle remained as endearing as ever but it was Irving’s account of his search for the Boar’s Head Tavern in Eastcheap, an area of the City of London well known to me, that most held my attention. This article tells the story of the events leading up to Irving’s writing of this delightful little piece, my attempt to follow in his footsteps and a quite unexpected connection with an ornate Wren church dedicated to Orkney’s best-loved and much revered Viking earl.

(Above) Ichabod Crane in Walt Disney's 1949 cartoon classic 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow' narrated by Bing Crosby. (Right) U.S Postage 1 cent stamp issued in 1940, one of 35 in the ‘Famous Americans’ series.

- In common with many an Orkney lad, Washington’s father, William Irving, who was born at Quholme, in Shapinsay, sometime around 1731, left home at an early age to follow the sea. It was during the French War, and while he was serving as a petty officer on an armed packet plying between Falmouth and New York, that he met and married Sarah Sanders, the grand-daughter of a West Country clergyman. In 1763 the young couple emigrated to New York where they raised a large number of children and William became a prosperous merchant. The Irvings were a close and devoted family and no-one seemed to be in any doubt that the youngest child, patriotically named Washington after the country’s first president, was blessed with the talent to become a great writer. By 1810, then aged 27, he had lost any enthusiasm he may had for a career as a lawyer and gratefully accepted the offer of a junior partnership in his brothers’ import/export business, which had branches on both sides of the Atlantic. Although not required to take an active role, Washington was to receive a 20% share of the profits, which would allow him to pursue his literary career. Peter Irving was in charge of the Liverpool office, based originally at 14 Water Street and later at 23 James’ Street, both conveniently situated for the docks, from where a wide range of manufactured goods was shipped to New York, to be sold by brother Ebenezer.

- At first all went well but the War of 1812 between Britain and the United States had a disastrous effect on trade. In addition to the obvious problems this caused for the family business, it was most likely personal depression following the death six years before of his fiancée, Matilda Hoffman, in whose father’s law firm he had worked, and unfulfilled literary aspiration that provoked Washington to leave New York and, on 25 May 1815, he embarked on board the ship Mexico for Liverpool. Soon after he arrived brother Peter, who was crippled with rheumatism, went to convalesce in Harrogate, leaving a very dispirited Washington to spend eight weary months preoccupied in “irksome and unexpected employment.” Despite strenuous efforts to keep the business solvent, the situation deteriorated and by January 1818 there was no alternative other than to declare themselves bankrupt. During the following February and March, they were summoned to appear three times before the Commissioners of Bankruptcy at the King’s Arms Inn, in Liverpool, which must have been especially humiliating for Washington who was only a minor party in the affair. However, by 22 June that same year, they were finally released from the burdens of commerce and, although initially somewhat downhearted, Washington was once more able to devote all his time to writing.

The Sketch Book by Washington Irving. Book cover depicting the headless horseman in 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow'.

14 Water Street, Liverpool. Oriel Chambers (1864) pioneered the use of prefabricated structural units in cast iron (Author's photograph).

- Even before the failure of the business Washington had often visited his sister Sarah and her husband, Alderman Henry van Wart, in Birmingham. One night in 1816, while staying at their house in Camden Hill, he sat up long after the van Warts had gone to bed. In fact he was still at the table when they came down next morning, weary but triumphant. Working throughout the night by candlelight he had produced a draft of Rip Van Winkle, which he read to his hosts over breakfast.

- It was most probably in the August of 1818, that Washington Irving made his now famous pilgrimage to Eastcheap in search of the Boar’s Head. This was the favourite haunt of his fictional hero, Shakespeare’s Sir John Falstaff, and the setting for what many consider to be the finest tavern scene ever written (Henry IV, Part II). But he was too late: the only trace of this ancient abode was the stone sign of a boar’s head built into the dividing line of two shops, which were occupied by David M’Kash, an Irish barber, and a firm of wholesale perfumers and wig merchants. The original premises had perished in the Great Fire of London (1666) but were soon rebuilt and flourished under the old name and original sign, until some thirty years before Irving’s visit when the tavern ceased to trade.

- Undaunted by this apparent set back, he decided to explore the area and was referred to a tallow-chandler’s widow, living opposite, who informed him that a painting of the old tavern could be found in St Michael’s Church, in nearby Crooked Lane. In the event this proved not to be the case but the sexton, who Irving had recruited as a guide, led him outside to a small adjoining cemetery which was overlooked by the rear windows of the old Boar’s Head. Here he was shown the tombstone of Robert Preston, a young barman at the inn, who it would appear had led an exemplary life and whose death in 1730 inspired a local poet to pen an epitaph that has become to be one of the best known in London. However, the sexton, no doubt sensing Washington’s disappointment at failing to find the picture he was seeking, offered to show him some artefacts from St Michael’s that were kept at the Mason’s Arms public house, in Miles Lane, which had taken the place of the “back parlour” at the Boar’s Head as the venue for meetings of the vestry (i.e. parish council).

St Magnus-the-Martyr Church, Lower Thames Street, London, hidden amongst high rise office buildings with the 'Monument' to the Great Fire of London (1666) in the background. (Author's photograph).

Original sign of the old Boar's Head, Eastcheap (1668) - Museum of London collection - not on display - (Author's photograph).

- The landlady of the Mason’s Arms, Mrs Edward Honeyball, seemed delighted with the opportunity to oblige and first produced a large japanned iron tobacco-box which had been passed round at vestry meetings for as long as anyone could remember. Irving handled this ancient relic with due reverence but it was the painting on its lid that most delighted him, for it depicted Falstaff with Prince Hal and the other madcap revellers outside the original Boar’s Head Tavern – exactly the sort of painting that he had hoped to find.

- While he “was meditating on it with enraptured gaze,” Mrs Honeyball handed him a drinking cup which he immediately realised was identical to the “parcel-gilt goblet” on which Falstaff made his loving, but faithless vow to Mistress Quickly (Act II, Scene I). Irving eventually took his leave from this old hostelry well satisfied with this brief adventure in search of the Boar’s Head Tavern, and feeling that his discoveries had contributed in no small degree to the subject of Shakespearean studies.

- The Sketchbook was published under the pseudonym of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., and first appeared in the United States in seven instalments, the third of which consisted of four short stories, including ‘The Boar’s Head Tavern, Eastcheap – A Shakespearean Research,’ came out in September 1819. It was published in England the following year, in two volumes, and was an immediate success both here and in America. Although there have since been greater writers, Washington Irving has every right to retain the title, “The Father of American Literature,” that was so enthusiastically bestowed on him during his own lifetime.

- A large area of the City of London, including part of Eastcheap, and Miles and Crooked lanes, was demolished to make way for the approach to John Rennie’s London Bridge, the one which was opened by King William IV on 1 August 1831 and now stands at Lake Havasu City, Arizona. One might reasonably suppose that during the passage of so many years some of the artefacts referred to by Irving would not have survived but happily this turned out not to be the case. My own pilgrimage to this historical part of London not only located all four of the items referred to above but I also managed to inspect them at close hand.

- The sign of the boar’s head was originally deposited in the Guildhall Museum before being transferred along with the rest of its collection to the award-winning Museum of London. Unfortunately, it was not on display at the time of my visit and is literally gathering dust in a huge storeroom in another part of the City. I was very fortunate to obtain permission to inspect this sign at close range and was surprised to find it measures only 19” x 16.5” x 9”, but weighs a ton! In 1831, when the church and surrounding buildings were pulled down, St Michael’s parish united with that of St Magnus-the-Martyr in Lower Thames Street. The publicity given to Robert Preston’s epitaph in The Sketchbook almost certainly contributed to his tombstone being considered of sufficient historical importance to warrant its preservation, and it now stands in the inner courtyard of St Magnus. The inscription reads:

-

- Here lieth the Body of ROBERT PRESTON

- late Drawer at the Boar’s-head Tavern

- in Great Eastcheap, who departed this life

- March the 16 Anno Domini 1730 Aged 27 Years.

- · **********

- Bacchus, to give the Toping World Surprize,

- Produc’d one Sober Son, and here he lies;

- Tho’ nurs’d among full Hogsheads, he defy’d,

- The charms of Wine and ev’ry vice beside;

- O Reader! If to Justice thou’rt inclin’d,

- Keep honest PRESTON daily in thy mind;

- He drew good wine, took care to fill his Pots,

- Had sundry virtues that outweigh’d his fau’ts;

- You that on Bacchus, have the like dependence,

- Pray copy Bob, in Measure and Attendance.

- The patrons of the Boar’s Head enjoyed the dubious reputation of being heavy drinkers and masters of the practical joke, and it is therefore hard to believe than a young barman with so many sober virtues would have inspired such a cleverly-worded epitaph. To my mind, Robert Preston was much more likely to have been a man with a Falstaffian disposition who drank himself into an early grave; an opinion that was shared by the little sexton.

Statue of St Magnus, St Magnus-the-Martyr Church, London (Author's photograph).

Headstone of Robert Preston, inner courtyard, St Magnus-the-Martyr, Lower Thames Street, London (Author's photograph).

- Together with the church plate of St Michael’s the oval-shaped tobacco-box also passed into the possession of St Magnus’ where it remains. I was most fortunate that the parish priest kindly allowed me to examine the “august and venerable relic,” which is exactly as described by Irving. Apparently the painting on the lid has been attributed to the well known artist and political satirist, William Hogarth (1697-1764),

- The 16th century parcel-gilt goblet was presented to the vestry of St Michael’s by Francis Withens, before 1633. This particularly graceful gourd-shaped cup, with a matching cover, stands about twelve inches high and is engraved with tear-drops; a design that is reputed to be based on Falstaff’s command to Mistress Quickly (also in Act II, Scene I): “Go, wash thy face” – the poor lady had been crying! Although it remains the property of St Magnus,’ the ‘Falstaff Cup’ is on permanent loan to the Treasury of St Paul’s Cathedral, and is currently on display in the crypt of that magnificent edifice.

- To have been able to see all four objects at such close quarters was a privilege indeed and, like Washington Irving, I too felt that it was a mission successfully accomplished.

- Irving returned home to New York in 1832, so ending a 17-year expatriation in Europe, which had included a month’s long tour of Scotland. It is surprising therefore, knowing his love of history and interest in regional writing, that he never visited Quholme (pronounce ‘kwy-home’), the small farm in Shapinsay,* where his father was born and his kinsfolk lived for generations. However, as a happy consequence of two City of London parishes being united, it is fitting that one brief episode in his long and fascinating life should now be so closely associated with an ancient church dedicated to Saint Magnus the Martyr, Magnus Erlendsson, Earl of Orkney.

- Washington Irving spent the last years of his life at Sunnyside, Tarrytown, New York, where he died, age 76, on 28 November 1859.

- This article was originally published in The Orkney View magazine and Sib Folk News, Newsletter of the Orkney Family History Society, Issue No 43 September 2007.

Sunnyside, Tarrytown, New York (Author's photogtraph).

Quholme, Shapinsay, Orkney, birthplace of Washington Irving's father (Author's photograph).

Irving Family Gravesite, Old Dutch Cemetery, North Tarrytown, New York, June 1994. (Author's photograph).

The author by the grave of Catriena van Tessel, model for Irving's Katrina Van Tassel in the 'Legend of Sleepy Hollow,' Old Dutch Cemetery, North Tarrytown, June 1994 (Author's collection).

- Note (*): My direct Russell ancestors (surname written as ‘Rusland’ or ‘Russland’ prior to 1805) had lived on the small island of Shapinsay, Orkney, since at least as early as the turn of the 17th century and therefore it is not unreasonable to assume that one or more of them would have been personally acquainted with Washington Irving’s father.

- **************************************

Number Three - A SYMBOL OF HOME AND FRIENDSHIP - reminiscences of Toc H in wartime Orkney

Woodwick House, Evie, Orkney, as it would have looked in the early 1940s.

- Toc H was born in the conflict of the Great War a hundred years ago and its work of reconciliation and service has continued to the present day. Now as we commemorate the 70th Anniversary of the end of the Second World War [2015], it seems particularly appropriate to pay tribute to a small band of dedicated men and women who served with this Christian organisation in Orkney and created a unique ‘home from home’ environment for so many members of the armed services in their time of need.

- Of all the places where Toc H provided at least some of the comforts and atmosphere of home for service personnel far away there can have been few where these were more appreciated than the bases and stations in Orkney. For the men from ships, at any rate, these bare windswept distant islands can have displayed little charm and provided no more than a godforsaken base with few amenities. The real Orkney was hidden away behind the hills surrounding Scapa Flow, while the treacherous Pentland Firth lay like a great gulf between them and all they loved best.

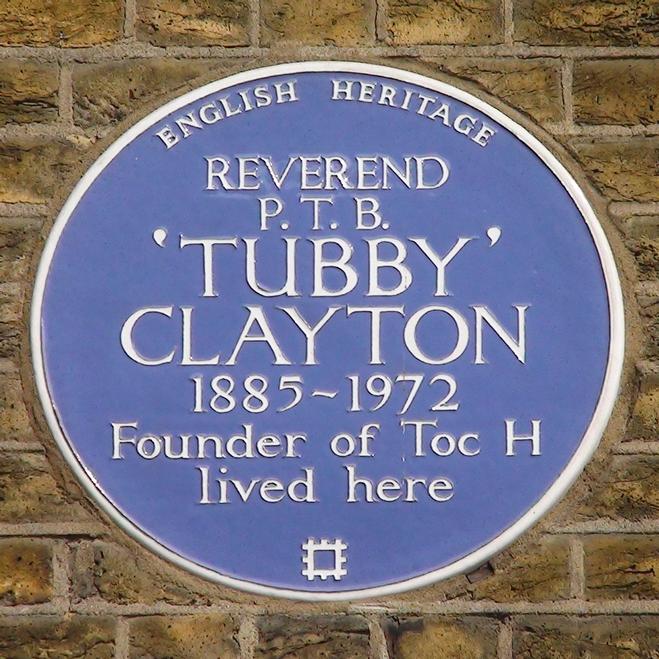

- Toc H was involved in many activities during this period. One of these was a direct result of talks which its founder padre, the Reverend Philip “Tubby” Clayton, had with survivors of HMS Royal Oak on the day following the tragedy of its sinking with such a heavy loss of life at anchor in Scapa Flow, in the early morning of 14 October 1939. He immediately realised the enormous need there was in so remote an area for some place of rest and recuperation for men who were suffering from shock, shipwreck or exposure, or who were not so seriously ill as to be sent south and yet were not well enough for duty.

- The idea met with approval of the naval authorities and Admiralty recognition was soon granted with facilities for transport and obtaining supplies, and the promise of a Sick Berth Attendant to assist in the work. A search was on the main island (actually called ‘the Mainland’) and among the big country houses not yet requisitioned by the military, Woodwick House, in the parish of Evie, set in the most beautiful surroundings, was considered perfect for the purpose of a convalescent and rest home. There flower beds and a vegetable garden, and very pleasant woods which in the springtime were filled with daffodils and bluebells, and were home to many nesting birds. A trout burn, overhung with rowans and willows, cascaded down to the sea into a secluded bay.

- Woodwick house was rented, furnished, for the duration of the war, and was equipped mainly through the generosity of the Pilgrim Trust, which also made an annual grant for as long as the house was open. In recognition of this timely and constant assistance in the inception of the scheme, it was officially called The Pilgrim House of the Toc H. The Canadian Red Cross, together with allowances from all three services and the invaluable help from Toc H branches, all made a significant contribution to its outstanding success. By March 1940 it was fully equipped and ready to receive its first ‘patients’.

- The length of stay varied, according to the nature of each one’s illness or injury, and it is difficult say in a few words just what Woodwick meant to the servicemen in Orkney. It was the only convalescent home in the islands, it was in the depths of the countryside with no cinema, no public house within easy reach, and only oil lamps and candles to illuminate the dark winter days. In fact, it was as a complete opposite to ship or shore establishment as can be imaged. The original number of beds, twenty-six, was later increased to thirty-four to accommodate the brave men of the Northern Patrol of the Atlantic and Russian convoys. In all, over 3,500 patients enjoyed a break at Woodwick.

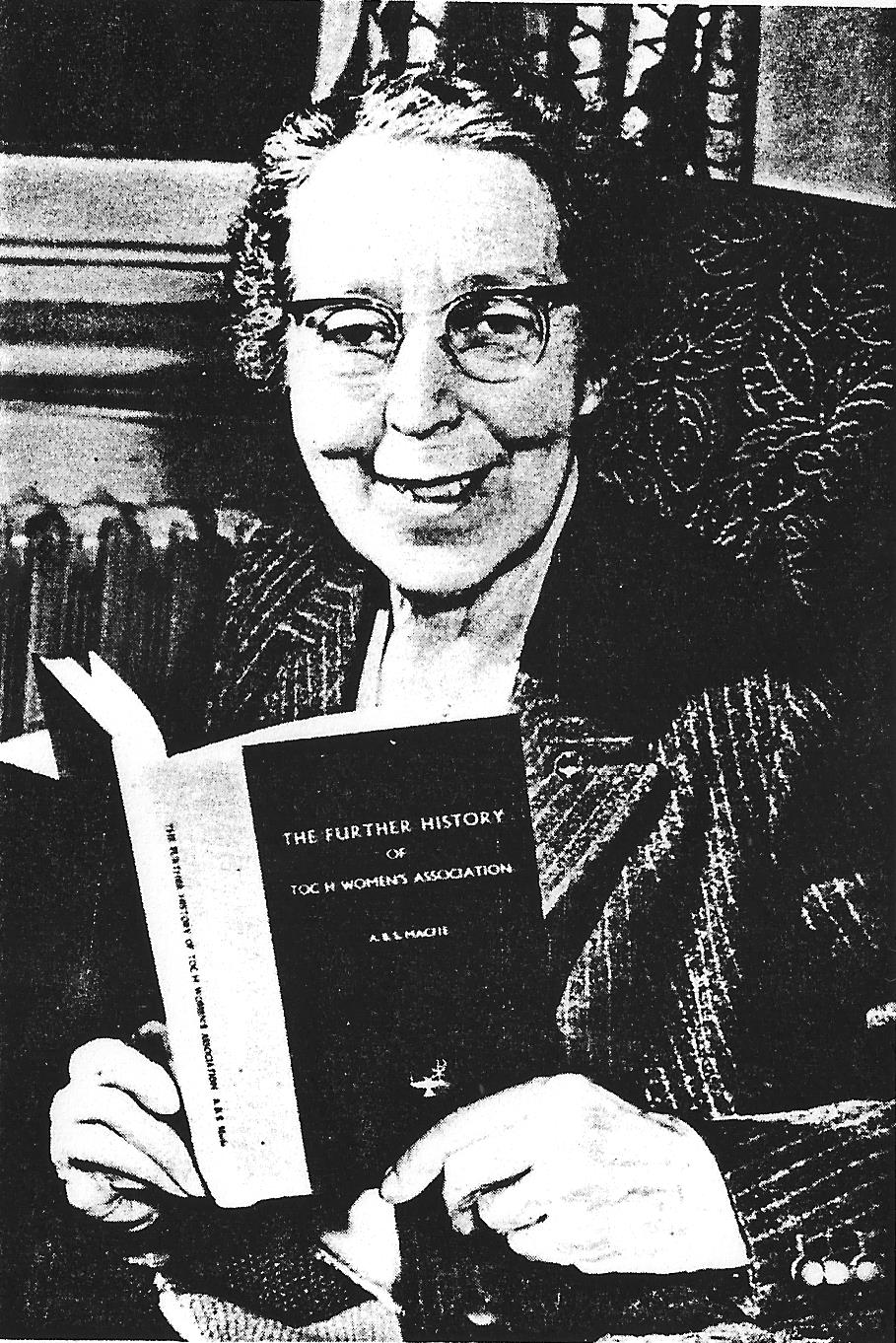

- Alison Bland Scott Macfie, the daughter of a wealthy Liverpool-based sugar refiner, who would soon become affectionately known as ‘Matron,” was appointed as the Warden. Miss Macfie, a devout Christian, was a founder member Toc H and first met Tubby Clayton in Poperinge. Belgium, at Easter 1917, when she was serving with the Voluntary Aid Detachment in the Ypres Salient. In a quiet determined way she got her ‘boys,’ the patients, to do what she wanted them to do. New arrivals were often greeted with the words: Act as if you were at home. To those who did not live up to the expected standards, she would say: “if you act like this home, then act as if you were at someone else’s.” Her kindly manner, shy wit, sense of fun and natural reserve did not entirely disguise signs of a strong and forceful personality, and she held very definite opinions on most matters. Like many others the war, Alison Macfie proved beyond doubt that she was the right person in the right place at the right time.

![Tubby Clayton [2]](https://www.menwithcuster.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Tubby-Clayton-2.jpg)

The Reverend Philip Thomas Byard "Tubby" Clayton CH MC (12 December 1885 – 16 December 1972), was an Anglican clergyman and the founder of Toc H.

Alison Bland Scott Macfie (25 December 1886 - 12 September 1963), founder of the Toc H Women's Section and Matron at Woodwick House (1940-1945).

- This gentle ‘saint’ was ably assisted by a Royal Navy Sick Berth Attendant, a cook, four housemaids-cum-general assistants and a gardener/handyman, who were soon hard at work providing hospitality for men and women from all the armed and nursing services. For this large family of many nationalities Alison Macfie and her staff created an ‘away from it all’ environment, with rest, good food and healthy recreation which was much needed at the time.

- Matron ran a very tight ship and the patients were actively encouraged to go for a walk before lunch. One particularly chilly morning several of the men were engaged in a game of pontoon in the lounge and were decidedly reluctant to leave the warm and comfortable surroundings. In her characteristic way she opened all the windows, insisting that they get some fresh air into their lungs, and it was not long before the through draft forced them out. Assuming they were going for a walk, she asked them to take her dog, Magnus, along them, to which the patients agreed, and they set off for the shore. However, they only got as far as an old boathouse and then proceeded to continue with their game of cards. Poor Magnus was tied to a post, and when lunch time arrived it dawned on the card players that the dog, which had been lying down for most of the two-hour session, was not the least bit tired. In order to conceal their deception they took it in turns to run the little dog round and round the boathouse: arriving back at the house they were greeted by a delighted Matron who was pleased to see Magnus panting for breath, and clearly well and truly exercised! Magnus, a mixed Shetland collie was, in fact, a bitch, and no-one knew why she was given such a noble and masculine name. This constant and faithful companion of Miss Macfie died at Woodwick House in the last year of the war and was buried in the woods where a small white marble headstone marks the spot. The simple epitaph reads: “Magnus/Good friend for 13½ years/1945.”

- For a time whist drives were held in the lounge and were well attended by local people. Unfortunately the staff seemed to be winning most of the prizes, which displeased the Matron, who ruled that in future only patients and guests would be allowed to hand in cards. Not surprisingly, the staff soon lost interest.

- There was no mains gas or electricity at Woodwick House and lighting was provided by Tilley (paraffin) lamps and candles. Lighting the lamps was a job for an expert and it invariably fell to the female members of the staff. For safety reasons the patients were forbidden to light the Tilley lamps as applying too much pressure could be very dangerous. Edith Harvey (the future Mrs Sinclair) and Ina Yorston (the future Mrs Greenwood), two of the housemaids, remembered this task well. First the lamp was heated with methylated spirits, and then carefully pumped to pressurise the paraffin. They gave out heat as well as light. Sometimes candles were placed in front of mirrors to provided extra light and on one occasion, during a spell of exceptionally cold weather, the small amount of heat generated actually cracked a large mirror. In time of war an extra seven years’ bad luck is something that they could have well done without!

Woodwick House, Evie, Orkney as it is today (above). The burn at Woodwick House (right)

.

- Although most of the naval patients were from the lower deck, at least one high-ranking officer spent some time at Woodwick House. An Engineer Commander of a famous battleship, often in Scapa Flow, having been brought low by a minor illness, was recommended by his medical officer to try a few days’ change at Woodwick. Rather reluctantly he agreed and duly found himself being transported in a state of some astonishment, and at great speed, in a drafty Ford V8 to a far corner of the Orkney Mainland. “What sort of place is this I’m going to?” he asked the driver’s Navy SBA: “It’s nothing like you’ve known before, sir,” was the reply. On returning to his ship a week later the Commander confirmed the rating’s view, and felt quite honestly “refreshed both physically and mentally and ….possessed with greater determination and energy in pursuit of my definite objectives.”

- The first SBA, 25 years-old Denis Truslove, from the West Midlands, arrived in April 1940. On returning to Naval Sick Quarters in Kirkwall (the Masonic Hall), from leave, he was advised that “he had been volunteered to work at Woodwick House for two weeks or until more permanent arrangements could be made” – in the event he remained there until January 1943! Truslove remembered his time at Woodwick House with a great deal of affection and had a wealth of interesting stories about the happy days he spent there.

- Many of his most amusing anecdotes centred on the heavy, wooden-bodied Ford V8 shooting brake, which was the chief mode of transport. According to Truslove, the tyres were the smoothest parts of this remarkable old vehicle, which nevertheless was capable of reaching 80 miles per hour along the stretch of straight road between Finstown and Woodwick.

- There was little actual nursing to be done at Woodwick and much of the SBA’s time was spent in collecting ‘bodies’ from, and returning them to, Scapa Pier and running errands for the Matron. When other duties permitted he would take patients out for a run to visit various places of interest, often using Matron’s own car. On one of these occasions an airman asked Truslove if he would make a short detour and drive him to his station so that he could pick up some long-awaited mail from home. On arriving at the camp the SBA was invited into the canteen for a cup of tea, while the airman took his leave on the pretext of collecting his post. The following morning Matron informed Truslove that she would be driving into Kirkwall to fill up with petrol. However, as the tank was now virtually full, with the ‘compliments’ of the RAF, he politely explained that her journey would not be necessary and recounted the events of the previous day. Matron’s reaction was somewhat severe, though not entirely unexpected: Petrol is brought into this country at great danger to help the war effort, not for dashing around the place sightseeing!”

- On another day Truslove was given the job of getting the wife of an army officer, who was helping out at Woodwick House, to the bank in Kirkwall before it closed at 2:00 p m, and as it was already close on half-past one there was no alternative but his ‘put his foot down’. As they were approaching Finstown he noticed what he assumed to be bags or sacks dumped on the grass verge, To his astonishment one of these ‘objects’ suddenly stood up and began to walk slowly across the road. A collision was unavoidable but thankfully – for the occupants that is – the old V8 was fitted with a sturdy pair of bumpers and the unfortunate sheep was impaled on one of the curve-shaped over riders, which prevented a potentially serious accident. Needless to say the ewe was killed. The badly-shaken officer’s wife, who was pregnant at the time, scolded the poor SBA with the words: If my baby is born with a sheep’s head, I’ll blame you!” Truslove duly reported the incident to the Police who took no further action as apparently accidents involving straying livestock were fairly frequent occurrences.

- Several years after the war while on holiday in Orkney, Denis Truslove was enjoying a quiet pint in the bar of the Pomona Inn in Finstown when his brother-in-law introduced him to a local farmer as: “The man who ran over your sheep.” Before Truslove had a chance to offer a single word of explanation, the aggrieved man snapped: “I never did get paid for it and sheep were £4 in those days.’ Some Orcadians are blessed with very long memories!

- While wondering around the garden one day Truslove stumbled across deep trench, measuring about four-feet wide. He mentioned his discovery to Miss Macfie who decided it could come in useful to store tin food and other non-perishable goods in readiness for a German invasion. She even went as far as to arrange for this hole-in-the-ground to be covered with sheets of corrugated iron and also choose plants to provide the best camouflaged. Fortunately its usefulness was never put to the test. The nearest that they ever came to having direct contact with the enemy was the time they were involved in a very hush-hush operation of washing salt water out of a ‘captured’ German parachute in the Woodwick Burn.

- No account of Woodwick House during the war years would be complete without reference to the near-legendary Dolly Dickson, the cook, who worked like a slave for the princely sum of £1 a week, plus board. In fact, Dolly was much more than a cook, she was a miracle worker, who produced the most tempting dishes out of the meagre collection of wartime rations. All the cooking at Woodwick was done on a large coal-burning range in the main kitchen. Dolly’s wonderful baking was done without any modern aids: she simply put her in the oven and somehow or other gauged the correct temperature and kept building the fire to maintain an even heat. A sailor from a destroyer wrote: “As to your cook, we are only awaiting her arrival on board before disposing of ours.” Dolly Dickson’s fame was spread through the Home Fleet, and far beyond.

- The ever-willing Denis Truslove came to her aid at the time she suspected a rat was getting into her kitchen through the bottom of a rotten window frame. “I’ll soon stop his little game” boasted the confident SBA. His plan of action was, indeed, a simple one. Several glass bottles were broken into small pieces and then forced into the offending gap. “That’ll cut his corns,” he exclaimed. Alas, it was not to be, for the very next morning the floor of Dolly’s scullery was littered with hundreds of shards of broken glass. Clearly the ‘rodent proof’ defences had been breached. Mercifully – for Denis that is – he suddenly found himself on an unscheduled trip to Kirkwall and was, therefore, not on hand to witness Dolly’s initial reaction to his failed attempt to rid her kitchen of this most unwelcome intruder. Soon after, the window frame was repaired and the much relieved cook was able once more to concentrate on her culinary duties.

- Unlike the Royal Navy, the other services did not make a direct financial contribution to the cost of running Woodwick House but, instead, supplied foodstuffs from their own sick quarters. The job of collecting these rations fell to the SBA, who would always ask Dolly Dickson if there was anything special she wanted. Arriving at the Army Hospital Centre on one particular occasion, Truslove told the sergeant cook that “We have some of your squaddies at Woodwick and they need feeding.” The NCO duly provided every item he had that was on Dolly’s list plus a few others to make up for those he hadn’t. Cook was delighted, Matron less so. “Truslove,” she sighed, “you should have only brought those things which were official!”

- Two of the greatest friends to the staff at Woodwick House were Davie and Bella Rendall, from the neighbouring farm of Walkerhouse. They supplied fresh eggs, milk, cheese, fowls for the table, vegetables and more. Many was the time that they gave a lift into town, which were much appreciated when the local bus only ran twice a week. Tubby Clayton, who was chaplain to the oil tanker fleet, often stayed with the Rendalls during his frequent visits to Orkney. His dog, Billy of Badminton, a beautiful brown pedigree spaniel, was presented to Toc H, Orkney, by H.M. Queen Mary (the Queen Mother) and spent a lot of time at Woodwick House. Another good friend was Mrs Mary Wood who did the laundry for the patients in her own home. It was a marathon task, all done by hand, as there was no electricity in any of the country districts at that time. The local Church of Scotland minister, Dr Alexander J. Campbell, regularly came for tea on Saturday afternoons. He was an accomplished storyteller and held his audience spellbound with his depth of knowledge of Orcadian and Scottish history, always referring to the early Norse inhabitants of these islands as ‘Vik-kings’, which was the cause of some amusement. The reverend gentleman was a most popular and welcome visitor: as a result, church attendance was usually quite high the following day.

- Every so often a Navy chaplain would come out to conduct a communion service. On one occasion his chauffeuse, a Wren, had driven off before the good man realised that the communion set was still in the boot of the car. In the event there was no need for concern as the resourceful Matron was on hand to help and quickly produced a sufficient number of small cream jugs and a bottle of Beaune to enable him to administer the sacrament.

- The Fleet Air Arm was stationed at Hatston and pilots honed their skills by flying Swordfish, nicknamed ‘flying bedsteads’, over the sea in the area between Evie and the island of Rousay. One morning a knock on the door of Woodwick House was answered to two airmen who enquired: “If it was possible to get a cup of tea and ring up Hatston?” They apologised profusely for their feet being wet which was due to the fact that they had just scrambled ashore, having ditched their aeroplane in the sea!

- Woodwick House possessed a greenhouse, which was a great asset to staff and patients alike. True, it faced the wrong ‘airt’ (direction), and was suffering from old age, decay and a lack of paint but nonetheless, it served a useful purpose. Being built against the dining-room wall it provided the first line of defence against blizzards and other inclemencies from the east; better still, thanks to Dolly Dickson’s ‘green fingers’, it was filled with a profusion of blooming geraniums and pelargonium’s, and clematis massed in one corner, and a genista to fill the other end with its sweet-smelling golden sprays all year round. And as the geraniums flourished so did the tomatoes, and the plant which seeds are noted for survival under even the most adverse conditions, was persuaded ‘to do its stuff’. It thus supplied some of the missing vitamins which an anxious Minister of Food had urged everyone to seek in a land where the turnip and the potato graced the table without rivals from November to May.

![Woodwick House [3]](https://www.menwithcuster.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Woodwick-House-3.jpg)

Woodwick House (1930s) - image taken from a postcard. Note the greenhouse next to the turreted extension on the left side of the building.

- With much encouragement, not altogether disinterested, from various medical officers of the Fleet Air Arm, tomatoes were planted in orange-boxes, which were still obtainable in greengrocers’ shops. At the end of the first summer the net result of all the care and attention was some very good chutney, and Principal Medical Officer was duly grateful for a small jar of it and the promise of something better next season, should he still be in the area.

- The following winters were fierce ones, even for Orkney, and in a full gale on 12 February 1943, the crash finally came: the whole greenhouse collapsing with much noise of splitting timber and breaking glass. However, with admirable promptness and resource the crew of HMS Kingston Amber, just returned that morning from a tour of duty with the Northern Patrol, flung themselves into action under the direction of SBA Harry Greenwood (who had recently replaced Denis Truslove), With old ladders, planks, oars, and bits and pieces picked up at random in the garden, pushed the fragments together, propped then up, and lashed them more or less securely in place with a new clothes-line just purchased for hanging out the washing on the drying green. In this hazardous engagement tin hats were worn by those who had them as a protection against falling glass, and all felt a sense of successful achievement, though somewhat dishevelled, when the job was done!

- For many weeks thereafter the whole company shivered grimly at mealtimes, the bitterly-cold east wind making its way all to easily through the wreckage of the ill-fitting door to the dining-room. They also thought longingly of tomatoes. So an appeal was made to the Royal Navy and the Army for help. For a month or more they were in suspense – who would come to the rescue? The Navy! The Army! Both? Or (horrible thought) neither! Then the GOC Orkney and Shetland went to see for himself, and quick on his heels came the Garrison Engineer, who was followed by Andrew Kirkness, a local man, who did odd jobs around the place, and the Royal Engineers. Andrew was an uncle of Mary Spence, one of the assistants, which made it a pleasant family concern.

- First, a day was spent contemplating the wreck, with the aid of cigarettes and cups of tea administered at regular intervals by Mary. Next came an army truck laden with ladders and trestles, paint, glass, putty and wood, and within a week the miracle was completed. The restored greenhouse was stronger than it had ever been.

- At the last came an unforeseen problem. A pair of linnets had built a nest in the clematis just under the roof, and a pair of blackbirds had settled in the upper branches of the genista, each nicely sheltered from the Orkney blasts. Both couples were expecting families in the near future and had serenely sat on their eggs, quite undisturbed by the work which went on around them. At the completion of the job, the workmen, in a dilemma, therefore decided to leave out a pane of glass at each end of the greenhouse for the convenience of the birds’ entry and exit. Andrew Kirkness would return later and put them in.

- A new difficulty arose when it was found that although the blackbirds would use the exit provided, they would not come home except through the open door, and much distress was caused if it was shut. Of course, the birds won the day, and the tomato plants had to do with cold feet until the time came when the fledglings gained their wings and flew out into the garden. Despite the early set back, that year produced a bumper harvest of tomatoes to brighten the bacon and embellish the salads.

- Germany surrendered in May 1945 and, happily, the services being provided by Woodwick House were no longer required. That summer Matron returned to London where in 1952 she became Founder Pilot of the Toc H Women’s Association. Following a short illness, Alison Bland Scott Macfie died on 12 September 1963, aged 76 years, at the County Hospital, Swaffham, Norfolk, and after cremation at Norwich, her remains were deposited in the crypt of All Hallows-by-the-Tower, London, EC3. A small oval-shaped, wooden plaque, depicting the Toc H lamp of the Women’s Association is inscribed:

- ALISON MACFIE

- Loved and Served this Church

- 1922-1963

- My Soul Doth Magnify The Lord

A blue plaque to 'Tubby' Clayton at 43 Trinity Square, Tower Hill, London. (Author's photograph)

A memorial plaque to Alison Macfie in All Hallows-by-the-Tower Church, London. (Author's photograph)

- The words of the popular wartime song ‘All the Nice Girls Love a Sailor‘ were certainly true as far as two of the staff at Woodwick House were concerned. Jean “Neen” Harvey, one the four original assistants, from the parish of Evie, married SBA Denis Truslove. The wedding was conducted by Dr. Campbell, who happened to be Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland at the time which, as far as Denis was concerned, is the equivalent of the Archbishop of Canterbury! Denis and Jean lived near Coventry, in the West Midlands. Ina Yorston, from the neighbouring parish of Rendall, married SBA Harry Greenwood in 1945, also in Orkney. Harry later became ordained a minister in the Church of Scotland, and he and Ina spent their twilight years in Perthshire.

- What happened to the other members of staff? Edith Harvey, sister of Jean, became Mrs Sinclair; Mary Spence, from Costa in Evie married Gordon Linklater, a local man, and like Edith Harvey and many others named a daughter, Alison, in honour of Miss Macfie, Neither Dolly Dickson, from Rendall, or Willie Scott, the gardener/handyman ever married. Denis and Jean, and Dolly and Willie, passed away many years ago. The fate of the others is not known to this writer.

- The noble motto of Toc H is ‘Bringing People Together’ and for five long years Alison Macfie and her devoted team did just that. To thousands of men and women from many nationalities Woodwick House, Evie, Orkney, was indeed A SYMBOL OF HOME AND FRIENDSHIP.

- Peter Groundwater Russell

- This story is based on a two-part contribution that was published in The Orkney View magazine (No. 60 June/July 1995 and No. 61 Aug/Sep 1995). An acknowledgement at that time was given to Mike Lyddiard, Director of Toc H, for kindly allowing me to quote freely from Alison Macfie’s memoirs and also to Ina Yorston Greenwood, Ann Herdman, Gordon and Leonard Linklater, Hazel Scarlett, Edith Harvey Sinclair, and Denis Truslove, who provided information and valuable assistance in the preparation of this article. The Orkney View, an excellent magazine, ceased publication with its 100th issue,

Number Four - A CLASH OF CULTURES AT RED RIVER - The Foss-Pelly Affair

The Hudson's Bay Company's flag.

The Hudson's Bay Company's logo - 'pro pelle cutem' meaning 'a skin for a skin'.

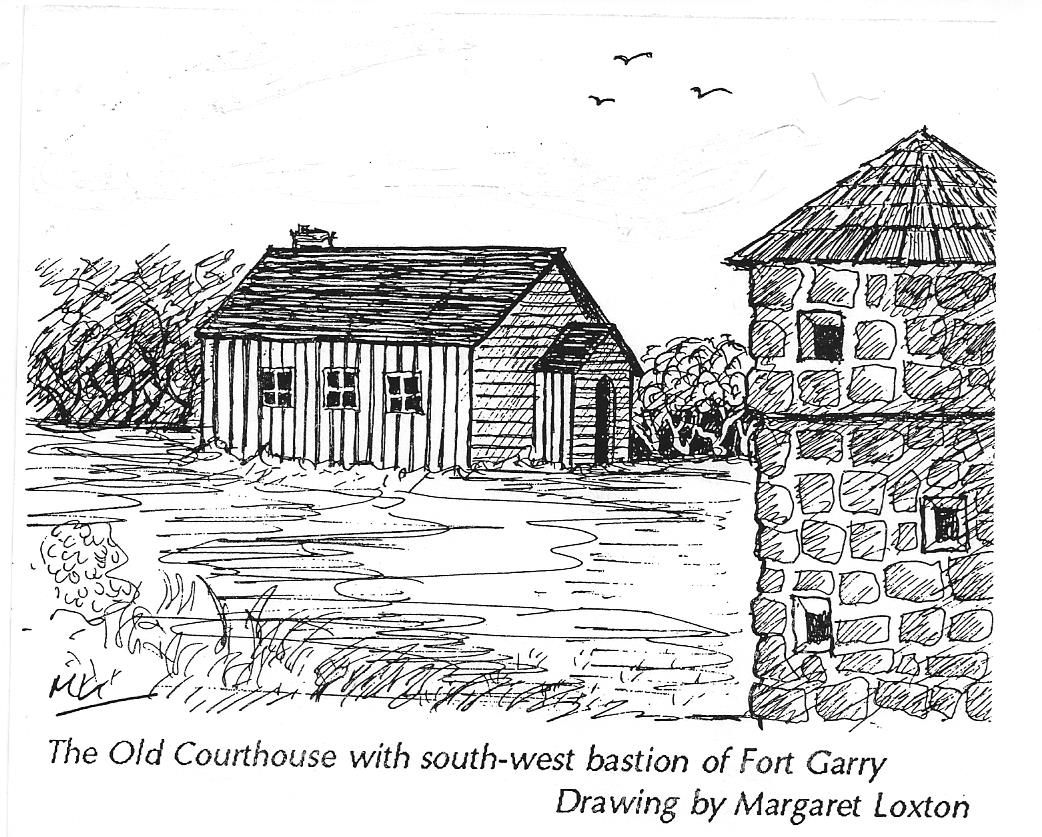

Thursday, 16 July 2015 marked the 165th Anniversary of the infamous Foss vs. Pelly slander trial in which John Ballenden and Anne Clouston, both from Stromness, a seaport in the islands of Orkney, which lie off the north-eastern tip of mainland Scotland, found themselves on opposing sides. The three-day hearing held in the Old Courthouse at Fort Garry, present-day Winnipeg, Manitoba, the headquarters of the Red River District of the Hudson’s Bay Company, became the sensation of the Canadian Territories. Although the specific lawsuit against the defendants was one of ‘defamatory conspiracy,’ this case brought into the open the racial tensions that had been growing for years between incoming whites and the integrated mixed-blood community. The cast of this wilderness soap opera was almost too stereotyped to be true, and its outcome seems more appropriate to a Victorian melodrama than to serious historical record.

- John Ballenden and Sarah McLeod

- John Ballenden, the third son of John Ballenden, a former high-ranking officer in the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), and Elizabeth Gray, was born in Stromness on May 26, 1811 and baptised by the Rev. William Clouston, a close relative of his wife’s future adversary. At the age of 18 he joined the HBC and served as an apprentice clerk at York Factory where he quickly proved to be a capable and popular officer.

- It was against a background of racial hostility that he married Sarah McLeod, the beautiful mixed-blood daughter of Scots-born Chief Trader Alexander Roderick McLeod. The wedding, which took place on 10 December 1836, was one of the social highlights of the year at Red River and showed that attractive and assimilated young mixed-blood women could aspire to social prominence through marriage to young company employees.

- In 1848 Ballenden was promoted to the rank of Chief Factor at Fort Garry and was happy to return to the Red River Colony after having spent the previous seven years at Sault Ste Marie in the Great Lakes region of Ontario. He was accompanied by his wife who soon established herself as a perfect hostess and her friends’ prediction that she was “destined to raise her whole caste above European ladies in their influence on society here” only served to fuel racial prejudices that were harboured by various sections of the community. Unfortunately John Ballenden was plagued with ill health since suffering a stroke on the long journey from Sault Ste Marie to Fort Garry, which left him partially paralysed. On the other hand Sarah’s vivacity and popularity with men excited much speculation and it was said that she was a woman “who must always have a sweetheart as well as a husband”. The following summer rumours were circulating that while John Ballenden was away from the district on HBC business Sarah was having an adulterous affair with Captain Christopher Vaughan Foss, a rumbustious Irishman, who had arrived at Red River the year before as second-in-command of a dubious rabble of army veterans who formed part of the British garrison. Local gossips, one of whom was the newly-arrived Mrs Anne Pelly (née Clouston), seized upon the opportunity to discredit Sarah Ballenden and in turn bring about her almost inevitable downfall.

- Augustus Pelly and Anne Clouston

- Anne Rose Clouston, the youngest child of Edward Clouston and Anne Rose Stewart, was born at Cleat, Westray, in 1831 and baptised on 29 May the same year. Her forbears included such notable figures as Earl Robert Stewart, William Balfour of Pharay, Archibald Stewart of Brugh and, not least, Sir Patrick Ballenden, who was an ancestor she shared with the Chief Factor at Fort Garry. Her father, a lawyer by profession, also acted as factor on his wife’s family estate of Cleat (originally known as Brugh) and at the time of Anne’s birth was living in the old mansion house there. A scrupulously honest, upright man, but perhaps too ingenuous for a lawyer, Edward Clouston finally settled in Stromness as agent for the HBC.

- On June 28, 1849 Anne Clouston set sail from Stromness on board the supply-ship Prince Rupert for York Factory, on Hudson Bay, to marry 26-year-old Augustus Edward Pelly, a second cousin of Sir John Henry Pelly, the London-based Governor of the HBC. The ceremony took place at York Factory on 28 August and four days later the happy couple left for Fort Pembina (present-day North Dakota, USA), a remote trading post on the upper Red River, some 70 miles south of Fort Garry, where Augustus was the Clerk in Charge.

- Clearly their aristocratic ways and fashionable mode of dress did not endear them to everyone at Red River, and may have contributed to the antipathy shown towards them by Captain Foss. According to one account the young Orcadian bride was a little too full of her own importance and naively assumed that her mere presence would guarantee a place near the top of the settlement’s social register. Apparently, she was much disconcerted to find that in spite of her connections she was obliged to give precedence to Mrs Ballenden, a woman who by both race and reputation she did not consider her social equal. Robert Clouston, Anne’s elder brother and a Chief Trader with the HBC, resolutely defended his sibling’s actions in a letter to a colleague in which he wrote: “…my sister is not a native – therefore must have the ill-will of that class. She has self-respect and acts in a manner entitling her to the respect of others therefore she must have the enmity of those who have lost the sense of shame.”

- Anne rather unwisely joined the growing band of gossips by spreading information gleaned from Catherine Winegart, Sarah Ballenden’s German maid, to discredit the Chief Factor’s wife, and demanded that the Governor of the Colony, Major William Caldwell, publicly censure her immoral conduct. This put Caldwell in a very difficult position as he had high regard for John Ballenden, was Captain Foss’ commanding officer, yet feared the Pellys’ London connections and hoped that the whole affair would soon be forgotten.

- Alas, it was not to be as in spite of Sarah’s servant mysteriously withdrawing her accusations, the gossip continued. Fuel was added to the fire when the mess steward, John Davidson and his wife made a sworn deposition which clearly implicated Sarah and Foss. Many of the European-born community and others began to openly express their views that the rather indiscreet and flirtatious behaviour of Foss and Mrs Ballenden at the mess table was proof of their intimate involvement. In retaliation Foss singled out the vulnerable nineteen-year-old Anne Pelly, almost certainly the youngest and probably the most recent arrival at Red River, in what may have been his way of ‘getting one over’ her husband and, in turn, the English establishment in London. He posted a public notice on the door of Fort Garry’s general store denouncing Mrs Pelly and proclaiming his intention to sue her for defamation of character. Things finally came to a head when she and her husband repeated the allegations in front of Overseas Governor of the HBC, George Simpson, during one his visits to Red River, and Foss promptly sued for defamatory conspiracy against them and the Davidsons, “to clear the reputation of a lady.”

- Foss vs. Pelly

- The three-day trial rapidly degenerated into a most disorderly affair. With some justification Augustus Pelly, who conducted his own defence, strongly objected to the composition of the court, as not only was the Recorder, Adam Thom, sitting as a judge in a case in which he had earlier acted as attorney for the claimant but all of the jury were either English-speaking Métis (mixed-bloods) or else married to native women – his objections were overruled. Thom was plainly biased towards Foss and the Ballendens and took every opportunity to ensure the Pellys’ conviction. Unsubstantiated accusations that Pelly was seeking revenge against Mrs Ballenden (the wife of his superior officer and mother of seven children) because she had allegedly rebuffed his advances towards her, and that he despised Foss for relieving him of a large sum of money gambling the previous winter both seem positively absurd.

- There is no evidence either to support the claim that Anne Pelly’s actions were racially motivated and consequently there is no reason to doubt that she would have considered it her duty to pursue the same course of action whatever the colour of Mrs Ballenden’s skin. Margaret Christie, the mixed-blood wife of Scottish clerk John Black, who also disapproved of Sarah’s unacceptable behaviour, numbered among Anne’s closest friends, and one of the witnesses for the defence was none other than the ardent Métis nationalist Jean-Louis Riel, father and namesake of the leader of the rebellion in 1869, which suggests that the Pellys had by no means alienated the entire non-white community.

- The trial was interrupted by an altercation in which Adam Thom bore some of the blame and the clerk was unable to record what was taking place. Order was eventually restored by Sheriff Ross and the case continued. Numerous witnesses were called, but there was little in the way of hard evidence. The court seemed more interested in pitting white against mixed-blood, and in proving or disproving Mrs Ballenden’s infidelity, than in considering the grievance filed against the defendants. Bearing in mind the make-up of the jury it was not entirely surprising therefore that, after deliberating for over four hours, they found the defendants guilty of defamation of character and Foss was awarded damages of £300 from the Pellys and £100 from the Davidsons. It is interesting to note that Foss never bothered to collect the £100 from John Davidson and, on the instructions of Governor George Simpson, Adam Thom’s commission as Recorder was revoked and he was never called on again to attend the court.

- According to Red River historian James Hargrave: “…probably no case ever brought before the Recorder’s Court has given rise to so much bad feeling, and such deplorable consequences, as did this ‘cause célèbre’.”

- The Aftermath

- Far from being the end of the matter, the trial only served to fan the embers of the racial prejudice and Sarah Ballenden continued to be shunned by at least half of the clergy and most of the European wives. Shortly after the trial John Ballenden travelled to Scotland for medical treatment, leaving his wife and younger children at the fort.

- Whether it was genuine or not, an unsigned note – believed to be in Sarah’s handwriting inviting “darling Christopher” to visit her – was found and passed to Eden Colvile who had succeeded William Caldwell as governor of the colony. Despite Mrs Ballenden strenuously denying all knowledge of the letter, many of her remaining allies, including Adam Thom, turned against her and she was increasingly ostracised by Red River society. To make matters worse Sarah’s health deteriorated so badly after the birth of her eighth child in 1851 that she was unable to accompany her husband to his new posting at Fort Vancouver (present-day Washington State, USA). John Ballenden stood by his wife even though there was pressure from several quarters for him to file for divorce. Alexander Ross noted sadly that: “If there is such a thing as dying of a broken heart, she cannot live long.”

- The well-known nineteenth century Orkney cleric, Dr. Robert Paterson, condemned “common gossip as a common liar,” but as it transpired that there was almost certainly some element of truth in what the Pellys had said their conduct in this unfortunate affair was largely vindicated.

- Deaths of John and Sarah Ballenden in Edinburgh

- In the summer of 1853 John Ballenden sent instructions to his nephew, Andrew Graham Ballenden Bannatyne, from South Ronaldsay, a former HBC employee, to take Sarah and the children to Edinburgh with the intention of meeting them there a few months later. John and Sarah did manage to enjoy a brief reunion in the Scottish capital that autumn, but two days before Christmas Sarah died of consumption – she was just 35 years of age. John Ballenden was back in charge at Red River the following season but on March 1, 1856 was forced to take early retirement from the HBC through ill health. He returned to Edinburgh where he died on 7 December the same year. Although they were both buried in the city, for some curious reason not in the same cemetery – Sarah was laid to rest in South Leith while John’s mortal remains lie in the nearby parish of Warriston. Does this mean that there may not have been the romantic reconciliation that previous accounts of this tragic tale would have us believe?

- The Pellys return to England

- At the time of the trial Augustus Pelly was the Clerk in Charge at Lower Fort Garry but the following season he was promoted to the rank of Chief Trader and transferred to the Upper Fort. A further advancement in his career followed two years later when he was appointed Trader in Charge at Fort Colvile, an important post 80 miles north of Spokane (present-day Washington State, USA), which was reckoned to be “the prettiest spot on the Columbia River.” The next summer the whole family sailed for England and stayed in the West Derby area of Liverpool, where the third of their seven or eight children was born. Augustus Pelly retired from the HBC’s service on June 1, 1855. Between 1857 and 1865 the Pellys spent several more years in Canada before finally settling in Birkenhead, Cheshire, which lies directly across the River Mersey from Liverpool.

- Anne Rose Pelly died of ‘a disease of the heart ending in dropsy’ at 27 Balls Road, Oxton, a district of Birkenhead, on March 16, 1874 and was buried in the Church of England section of the Flaybrick Cemetery in the town, where only the sunken base of a granite tombstone has survived. There is no record of Anne ever returning to Stromness.

- Shortly after his wife’s death Augustus moved to the neighbouring suburb of Claughton, before leaving the district in the early 1890s for an unknown destination. On May 17, 1907, then age 84, he lapsed into a coma and died at 57 Disraeli Road, Putney, southwest London, a lodging house run by a Mrs Abigail Croft. Four days later Augustus Edward Pelly was buried in Putney Vale Cemetery, which forms the northern boundary of Wimbledon Common, far removed in both time and space from the bitter conflict that caused so much distress among the small fur-trading communities that once lined the banks of the Red River.

- This article was originally published in The Orcadian newspaper, Kirkwall, Orkney.

Number Five - CANADA BECKONED - AT £17 A Year - Andrew Groundwater (1824-1917)

- Extracted from The Orcadian, Thursday, August 19, 1993

- CANADA BECKONED – AT £17 A YEAR

- Those were the prospects for Orcadian labourers

- This year marks the centenary of the death of the Orcadian Arctic explorer Dr John Rae – commemorated by the exhibition “No Ordinary Journey” at the Tankerness House Museum in Kirkwall. But Rae, of course, was not alone in going to Canada from Orkney in the 19th century. Here Peter Groundwater Russell tells the story of Andrew Groundwater who served nine years with the Hudson’s Bay Company. He had the distinction of being born in the same parish as Rae, serving under him in Canada and travelling home aboard the same ship in 1854.

- Andrew Groundwater was born on June 12, 1824, at the farm of Piggar in the parish of Orphir, the ninth child of William Groundwater and Catherine (née Robertson). When he was seven years old his father died and his mother was left with six young children to support. She managed to carry on for a few years, until Piggar became incorporated into Swanbister, one of the largest farms on the Mainland of Orkney. The family then moved in with James, the second eldest son, who had recently acquired the tenancy of the farm of Dykend on the Smoogro estate.

- Groundwater was living at Scapa at the time of his marriage to Isabella Thomison, younger daughter of William Thomison, a farmer in Flotta, and Mary (née Barnett); the wedding took place at Crooksteeths in Linnadale, Orphir, on September 18, 1845. Andrew and Isabella set up home in the neighbouring district of Clestrain where their first child, William, was born on January 17, 1846.

- The Hall of Clestrain was the birthplace of Dr John Rae, surgeon, Arctic explorer and chief factor with the Hudson’s Bay Company, whose death 100 years ago is currently being commemorated by the exhibition “No Ordinary Journey” at the Tankerness House Museum in Kirkwall. Groundwater was later to serve under Rae at Fort Good Hope, on the Mackenzie River, and they would meet again aboard the Company’s vessel Prince of Wales.

- Since the beginning of the 18th century Orkney had been a favourite recruiting ground for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Many young men were attracted by the prospects of a higher standard of living and a better chance of saving money than a labouring life at home was likely to offer. Supplies for their establishments in North America were shipped annually to the Hudson Bay supply depots by the company’s vessels which left the Thames in early June and arrived in Hudson Strait as the ice was giving way to open water.

- In 1847, Andrew Groundwater signed a five-year contract with the company as a labourer at a salary of £17 per annum. On June 24 he boarded the Prince Rupert at Stromness which, together with the Prince Albert and the Westminster sailed to York Factory on the west coast of Hudson Bay. Isabella was then carrying their second child who was to be born seven months later and named Alexander, after one of Andrew’s older brothers. A full account of Alexander Groundwater’s life can be found in Memories of an Orkney Family by Henrietta Groundwater, The Kirkwall Press, (1967).

- Life was hard in the wilderness of northern Canada, with nine months of winter followed by three months of rain and mosquitoes. Relief from the dreary monotony in this unrelenting environment was often found in alcohol, although each Hudson’s Bay Company post had a “bachelors’ hall” where card and dice games and dancing took place.

- After an initial winter at York Factory, supply depot and headquarters for the company’s Northern Department of Rupert’s Land, Groundwater was transported to the Mackenzie River District. He then wintered at Fort Resolution, Great Slave Lake in 1848-49, and at Fort Good Hope from 1849 to 1852. Fort Good Hope, close to the Arctic Circle, is over 800 miles north-west of Lake Athabasca and was one of the company’s remotest outposts.

- When Groundwater’s five year contract expired in 1852, he signed on at Fort Simpson, headquarters of the Mackenzie River District, for a further two years of service, at an increased salary of £22 per annum. This second term was spent at Fort Resolution which enjoyed the reputation of being “one of the company’s neatest and cleanest establishments.”

- In 1854 Groundwater retired from company service, taking passage home from York Factory aboard the Prince of Wales, which sailed on September 21 and arrived off Deal 32 days later. A fellow passenger was the celebrated Dr John Rae; it had been in June, 1850 while Groundwater was serving at Fort Good Hope, that Governor George Simpson appointed Rae as chief factor for the Mackenzie River District, although most of his time was devoted to further Arctic exploration.

- Rae, still flushed with success over his part in solving the mystery surrounding the disappearance of Sir John Franklin, would have been hoping to write the report of his recent exploration of the west coast of Boothia and draw a chart of his discoveries. Both were eagerly awaited by the Honourable Committee in London, but the voyage across the Atlantic proved to be so stormy that he was unable to complete either of them.

- It was while Rae was surveying the Boothia Peninsula the previous April that he had met an Eskimo wearing a gold-braid naval cap band. Through him, and others, Rae became the first European to learn of the fate of Sir John Franklin’s doomed search for the North West Passage, a search which had ended long before the last members of this expedition died of scurvy and starvation near the mouth of Back’s Great Fish River in the spring of 1850. Rae purchased 45 objects from the Eskimos, including Sir John’s Order of Merit and a silver plate engraved with his name, and all of these artefacts were brought back to England in the York Factory packet box aboard the Prince of Wales.

- Groundwater returned to a croft in Linnadale and to his wife and two sons, the younger of whom, then aged six, he had never seen! Necessity forced him to turn his hand to a variety of different jobs, including those of a quarry labourer and a mason, which he combined with work around the croft.

- Over the next eight years Andrew and Isabella were “blessed” with five more children. With such a large family to support, making ends meet was not easy, and for a second time he applied to the Hudson’s Bay Company for employment.

- In late December, 1863, Edward Clouston, the company’s agent in Orkney, wrote to Thomas Fraser, the company’s corresponding secretary in London: “… I have an application for a re-engagement as a labourer by Andrew Groundwater who retired in 1854 after being seven years in the service – the whole of which was at Mackenzie River under Messrs Macpherson and Bell and Dr John Rae and Mr Anderson, successively, with the exception of the first winter of his contract spent at York Factory under Mr Hargrave. His age was 39 last June which is beyond the usual limit – but he is a healthy looking man, and to all appearance still fit for the service which however would have to be medically certified before contract being entered into. I should feel obliged by being informed whether he may be re-engaged at your earliest convenience – as he speaks of having some other arrangements in view (possibly emigration to Australia) if his present application cannot on account of age be granted.” Fraser replied that: “… Groundwater had come home with a character as ‘a good servant’ and if his health proved satisfactory after a medical examination, he might be re-engaged.” Accordingly, on January 26, 1864, he was taken on as a labourer for a term of five years’ employment at £22 per annum.

- In June that year he travelled from Stromness to York Factory aboard the 524-ton Prince of Wales. Of his five-year contract, Groundwater served only two years, which were spent in the Lake Island area, supervised by Chief Trader James Green Stewart in charge at Oxford House, Oxford Lake (present-day Lake Manitoba) in the York Factory District.

- No particular reason has been found for his premature retirement in 1866, but it may have been on compassionate grounds or even through temporary ill-health. On September 25, 1866, Chief Trader J. W. Wilson, in charge at York Factory, sent to the Company in London a list of the retiring employees with notes as to their characters; unfortunately this document has not survived. Wilson’s letter noted that of the 30 servants “retiring or discharged” only 16 had actually completed their term of contract, “the remainder being sent home either in consequence of unfitness for work or refusing duty.” Wilson’s letter continued at length regarding labour troubles noting: “… Dissatisfaction with the service is nearly universal among Europeans, although of late years both their rations and wages have been better than formerly.”

- For each of the two years he served, Groundwater was paid a gratuity of £2 in addition to his salary. He took passage from York Factory aboard the company’s ship Prince Rupert which reached London on October 31, 1866.